Hope you had a happy and harmonious (i.e., politics-free) Thanksgiving. This year, for the first time in decades, my bride and I sheltered in place instead of joining the nationwide mass migration to visit kids, grandkids and relatives. We skipped the home-cooked turkey, too, and dined out on professionally-prepared Thanksgiving cuisine. Not exactly a Norman-Rockwell-Hallmark-Channel family event, but not bad.

Meanwhile, The American Spectator published my article about the Office of Inspector General’s report on the many deficiencies of the FBI’s faux program for validating the reliability of its confidential informants. You can access it by clicking this link. Or you can read it – minus reader comments – below.

Also, today’s American Thinker published an excellent article on the Bidens and their Ukraine scams by Texas physician and attorney John Dale Dunn. In it he reprises parts of my “Impeachment Defense” article from The American Spectator. Dr. Dunn’s very fine article expands on the Biden corruption narrative and is well worth a read. You can access it by clicking on this link.

Anyhow, here’s my latest in The American Spectator.

The FBI Lets Itself Be Taken for a Ride

Long ago, as I began my career with the U.S. Justice Department’s Organized Crime and Racketeering Section, a veteran FBI agent explained to me the First Commandment in the war against the mob. “A confidential informant is like fire. Properly controlled, both can be useful. Uncontrolled, they will cause disaster.”

Not long after that, a pair of Boston FBI agents and an Irish thug proved the wisdom of my mentor’s advice.

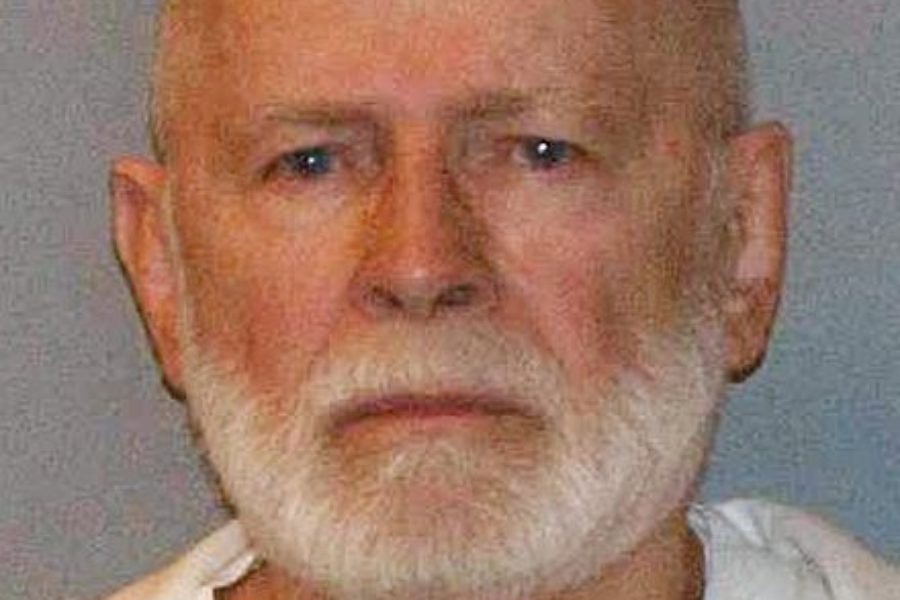

In the mid-1970s, John Connolly was a young, ambitious FBI agent who devised a hugely flawed plan to eliminate the Boston family of La Cosa Nostra. A South Boston native, Connolly cut a deal with one of his childhood heroes, Jim “Whitey” Bulger, a vicious mobster. The deal? The FBI would use information from Bulger to go after the Italian Mafia. This cost Bulger nothing and allowed him to direct the FBI against his competition.

But there was a major problem with this arrangement. Since Connolly had no control over his informant, and no one was effectively supervising Connolly, it was inevitable that Bulger would gain the advantage over the FBI.

Using information from Bulger and his hitman associate, Steve “The Rifleman” Flemmi, the FBI took down the Italians amid banner headlines. Meanwhile, the Massachusetts State Police and the Drug Enforcement Administration were investigating Bulger and Flemmi for extortion, drug dealing and assorted felonies.

It later emerged that, to protect the informants and encourage their cooperation, Connolly and his supervisor, FBI Special Agent John Morris, tipped Bulger and Flemmi to the other law enforcement agencies’ wiretaps and investigations. With these obstructions of justice, Connolly and Morris delivered themselves into the hands of their informants who could threaten to expose the agents and, if caught, trade them for leniency. To cement his hold over the agents, Bulger (with Connolly as a middleman) gave $7,000 cash to Morris. For this chump change, Bulger got to add bribery to his arsenal of threats against the agents.

Protected by the FBI, Bulger and Flemmi ran roughshod over anyone who got in their way. Honest citizens who sought the FBI’s protection were scared off by Connolly. The FBI debriefed one potential witness for weeks before he was jettisoned as supposedly unreliable. Shortly thereafter, the witness was murdered.

With much to lose if it admitted the truth, the FBI obdurately ignored the mounting evidence of this corrupt relationship and continued to back Connolly and Morris.

But then the dam finally broke and arrest warrants were issued for the informants. The FBI insisted that it – instead of the State Police – would execute the arrest warrant on Bulger. But, mysteriously enough, Bulger disappeared the night before his scheduled arrest. Though he was placed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list, he wasn’t taken into custody until 16 years later.

While Whitey was on the run, Special Agent Connolly was indicted in 1999 for alerting Bulger and Flemmi to investigations, falsifying FBI reports to cover their crimes, and accepting bribes. The following year he was indicted for racketeering, obstruction of justice and murder charges arising out of his corrupt relationship with Bulger and Flemmi. In 2002 he was convicted of racketeering and sentenced to ten years in federal prison. In 2008 he was convicted in Florida state court of murder and sentenced to 40 years’ imprisonment. This last conviction was based on evidence that Bulger had murdered a business associate after receiving a tip from Connolly that the victim was being investigated by police for his relationship with Bulger’s gang.

There’s more to the corrupt saga of Special Agents Connolly and Morris, but you get the idea.

So, what has the FBI done to effectively prevent a similar recurrence of Connolly’s unholy alliance with Bulger? According to the Justice Department’s Office of Inspector General’s recently released Audit of the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Management of its Confidential Human Source Validation Processes , not much.

Citing the FBI’s disastrous experience with Whitey Bulger, the OIG’s report states that “[b]ecause of the important role of CHSs [Confidential Human Sources – today’s bureaucratic term for informants], vetting the credibility of CHSs and assessing the veracity of the information they provide is critical to the overall integrity and reliability of the FBI’s CHS program. This process, known as validation, is a fundamental responsibility of intelligence collectors, including the FBI.” The report further states that such validation is “essential” because it “assists in ensuring that information obtained from any CHS is accurate, authentic, reliable, and free from undisclosed influence.”

The OIG found that the FBI’s vetting process did not comply with the Attorney General’s Guidelines Regarding the Use of FBI Confidential Human Sources which “govern the use of CHSs by the FBI. As a result of lessons learned [from l’affaire Whitey], the guidelines were most recently revised in December 2006, including the creation of special provisions for long-term CHSs and a Human Source Review Committee (HSRC) to approve a long-term CHS’s continued use.”

Translated into English, the report is stating that, in response to the Connolly-Morris-Bulger-Flemmi cluster coupling, the Justice Department and FBI did what all federal bureaucracies do: they made up some rules and appointed a committee. And guess what? The OIG found that the FBI “inadequately staffed and trained” committee personnel who were “conducting long-term validations and lacked an automated process to monitor its long-term CHSs.” And, for good measure, the OIG found “deficiencies in the FBI’s long-term CHS validation reports which are relied upon by FBI and Department of Justice (Department or DOJ) officials in determining the continued use of a CHS.”

What a surprise. When presented with a serious problem, a federal bureaucracy issued some regulations, appointed a committee to enforce them, spent tax dollars, spun its wheels and accomplished nothing. Who could have seen that one coming?

The report runs 56 pages and makes for depressing reading. The bottom line is that the FBI – either by sloth, incompetence or willful design – lacks a well-maintained data base which would enable it to determine the accuracy and reliability of its sources’ information as well as whether those informants are free from pernicious influences.

In the 1990s, Whitey Bulger played the FBI for fools. And, in 2016, after being dropped by the FBI as an informant for violating its protocols, British spy Christopher Steele fed the Trump-Russia collusion hoax to the FBI and DOJ leadership. Whether an effective validation process would have prevented Steele from conspiring with these leadership elements is necessarily a matter of speculation. But maybe – just maybe – a functioning and effective validation process might have documented and exposed the unreliability of Steele and his disinformation and made it far too risky for FBI Director James Comey and others to falsely swear to its truthfulness before the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court in order to obtain a warrant to spy on Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, his transition team and his early days in the White House.

But we will never know since, under the leadership of FBI Directors Comey and Robert Mueller, the FBI never implemented such a functioning validation program. All of which raises a key question.

Why not?

George Parry is a former federal and state prosecutor. He is a regular contributor to the Philadelphia Inquirer and blogs at knowledgeisgood.net. He may be reached by email at kignet1@gmail.com.

Leave a Reply

Leave a reply.