I want to thank all of you who have noted my recent absence from these pages and took the time to inquire about my well-being. Fear not. I’m in the Free State of Florida hanging out on the beach and in watering holes swapping war stories with old friends. No masks, vaccine passports or Covid restrictions of any kind. It’s like a time trip back to an America that existed before the Wuhan lab leak.

Thanks to two days of rain and chilly (65 degrees F) weather, I finally found time to sit down and bang out a piece that ran in yesterday’s The American Spectator. It’s about the upcoming trial of the desperadoes facing federal charges for allegedly planning to kidnap Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer.

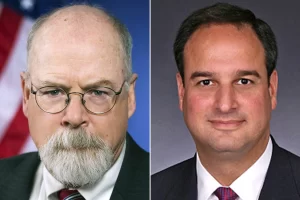

Believe it or not, the bearded muscle man pictured above is the Special Agent who ran the FBI’s investigation of the Whitmer kidnap plot. As you will see below, after he signed the criminal complaint charging the would be kidnappers, he became the face of the prosecution as he testified in pre-trial proceedings. As I describe in the article, he was then arrested for beating and choking his wife when she complained about his forcing her to attend a swingers’ party. The arrest ended his FBI career.

You can view a brief and informative television news report about the Special Agent’s arrest by clicking on the picture below. As you will see, in addition to going to a swingers’ party, feloniously assaulting his wife and getting arrested, this genius – while he was at the very center of a high profile and politically sensitive prosecution – took to social media to proclaim to the world his vitriolic contempt for President Trump and his supporters.

This kind of moronic behavior raises serious questions about the hiring standards of today’s woke FBI.

Here’s the article.

Your FBI in War, Peace, and Swingers’ Clubs – The American Spectator | USA News and Politics

Faced with an apparent short supply of crime, today’s woke FBI has risen to the challenge by encouraging and enabling the delusional among us to act out their anti-social fantasies as informants, undercover agents, and hidden electronic devices document and record the results. In doing so, the FBI has adopted what used to be known in the old Soviet Union as “provocations” in which unsuspecting subjects were induced by agents provocateurs to commit acts of subversion against the state. Once the target picked up the planted but “unauthorized” loaf of bread or uttered the provoked subversive comment, the trap would spring shut and another enemy of the state would be shipped off to the Gulag. Or worse.

That was how the tyrants who ran the Soviet Union used provocations to ferret out and punish wrong-thinking counter-revolutionary elements. But things are different here in the USA. Our valiant G-men [insert appropriate gender identifier here] would never operate like the old KGB. Right?

In America, such provocations are subject to the defense of entrapment which holds that government agents may not originate a criminal plot, implant in an innocent person’s mind the disposition to commit a criminal act, and then induce commission of the crime so that the government may prosecute. A valid entrapment defense has two elements: (a) government inducement of the crime and (b) the defendant’s lack of predisposition to engage in the criminal conduct.

Generally speaking, whether or not a defendant has been entrapped is an issue to be decided by the jury. So, how is entrapment proved?

First is the issue of what constitutes inducement. Back in the 1930s, the U.S. Supreme Court held that neither the government’s mere solicitation to commit a crime nor its use of artifice, deceit, or pretense in doing so is sufficient to constitute inducement. Since then, federal circuit courts of appeal have held that inducement requires proof, at a minimum, that the government used persuasion, mild coercion, or pleas based on need, sympathy, or friendship. But, even then, such actions must have created a substantial risk that an offense would be committed by a person other than one ready to commit it.

This brings us to the issue of predisposition which requires the jury to focus on, in the words of the Supreme Court, whether the defendant “was an unwary innocent or, instead, an unwary criminal who readily availed himself of the opportunity to perpetrate the crime.” Consequently, the prosecution must prove that the defendant was disposed to commit the crime prior to first being approached by government agents. According to the Supreme Court, predisposition may be proven by evidence showing that the defendant readily engaged in criminal conduct by promptly accepting an undercover agent’s offer of an opportunity to commit the crime.

In short, no matter how outrageous or overbearing the government’s inducement may be, if the defendant was predisposed to commit the crime, the entrapment defense will fail.

In recent years, the entrapment defense has been the subject of a great deal of litigation. And, given the FBI’s targeting of American citizens who dare to oppose governmental abuses at all levels, much more is on the way.

So it is that, in today’s dystopian social-networked surveillance state, the ever-watchful FBI has been able to encourage, coax, and nurture what used to be otherwise harmless political complaints and grievances into full-fledged conspiracies to commit federal crimes. This approach has the added advantage of producing crimes that are easily solved since law enforcement has had a direct role in planning, executing, and monitoring them.

Take, for example, the alleged nefarious plot to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer.

In October 2020, as the presidential race was reaching a climax and Whitmer continued to impose her draconian, ruinous, and oppressive COVID restrictions on Michigan’s citizenry, the U.S. Department of Justice filed kidnap conspiracy charges against a small group of men who were apparently fed up with her dictatorial ways.

According to the prosecution, the men were upset about the damage being caused by Whitmer’s COVID lockdowns and policies. They allegedly plotted to kidnap her as part of a fanciful plan to overthrow the Michigan state government.

According to media reports, the FBI recorded a telephone call in which one of the defendants discussed needing “200 men” to storm the state capitol and take Whitmer and others hostage.

In addition, with the help and encouragement of numerous informants and undercover operatives, the defendants engaged in other overt acts to further their plot. Reportedly, all of these overt acts have been carefully recorded, documented, and catalogued by the FBI.

Since the indictment, the prosecution has encountered a few difficulties.

First, the FBI’s lead informant, a convicted felon who was key to planning and implementing the kidnap plot, has pled guilty to illegal possession of a firearm. He has been sentenced to probation. Whether he will testify at trial is an open question.

Second, an FBI special agent at the center of the investigation has been fired after he was charged by local authorities with assault with intent to do great bodily harm to his wife. According to an affidavit filed by the Kalamazoo County Sheriff’s Office, the special agent and his wife attended a swingers’ party at which he had several drinks. Mrs. Special Agent didn’t like the party which led to an argument on their way home.

Once there, he allegedly straddled her in bed and then, in the words of the affidavit, “grabbed the side of her head and smashed it several times on the nightstand.” The affidavit also states that she attempted to grab his beard to free herself at which time he began choking her with both hands. She then grabbed his testicles which — quite understandably — ended the assault.

According to the affidavit, Mrs. Special Agent had bloody lacerations to the right side of her head, “blood all over [her] chest, clothing, arms and hand,” and “severe” bruising to her neck and throat.

Sheriff’s deputies arrested the fugitive special agent in a supermarket parking lot. After being read his Miranda rights, he refused to give a statement. The charges against him are punishable by up to 10 years confinement.

Two points here.

First, we are obviously not dealing with J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI. A swingers’ party? Wife beating? Trying to choke her out? Fleeing the scene of a crime? What the hell?

Or, to paraphrase Simon and Garfunkel, where have you gone, Inspector Erskine? Our nation turns its lonely eyes to you.

Second, prior to the alleged assault on his wife, the special agent had supervised and run the undercover investigation of the kidnap plot. Now that he has been fired by the FBI, it is doubtful that he will appear as a prosecution witness which will, of course, complicate the presentation of the government’s case.

On the other hand, if the defense is up for some cheap thrills and a great deal of fun at the government’s expense, it may want to subpoena the no longer special agent as a hostile defense witness. Who knows? Having been fired, this guy may feel justified in turning on his former employer.

And then, in addition to the prosecution’s informant and case agent difficulties, the defendants have moved to dismiss the charges based on “egregious overreaching” by the government.

“The key to the government’s plan was to turn general discontent with Governor Whitmer’s Covid-19 restrictions into a crime that could be prosecuted,” defense counsel wrote in the motion. “The government picked what it knew would be a sensational charge: conspiracy to kidnap the governor. When the government was faced with evidence showing that the defendants had no interest in a kidnapping plot, it refused to accept failure and continued to push its plan.”

The motion further states that “the government initiated this case, despite the fact that it knew there was no plan to kidnap, no operational plan, and no details about how a kidnapping would occur or what would happen afterward. The facts show that there was no conspiracy. In the alternative, because the government overreached and committed serious acts of misconduct against defendants who had repudiated the government’s suggested wrongdoing, the defense can establish entrapment as a matter of law.”

Crucially, the motion also avers that the defendants were not predisposed to commit the crime and that the prosecution cannot prove otherwise.

Now it’s important to note that the above is what defense counsel claim the evidence will prove. What actually happened remains to be seen. But, assuming the defense’s factual averments are substantially true, were the defendants legally entrapped?

Given what we know so far about the alleged plot, it’s hard to see how the defendants could have engaged in it to any extent — no matter how slight — without being predisposed to do so. And that would be fatal to an entrapment defense.

But why did defense counsel move for a pre-trial dismissal of the case? Are they up to something other than an entrapment defense to be heard by a jury?

I suspect that defense counsel know that at trial they won’t be able to overcome the evidence of predisposition. That is why, despite their claim to the contrary, their motion is based not so much on entrapment but on a parallel claim of outrageous government conduct. This legal doctrine presupposes a defendant’s predisposition but is based on conduct of law enforcement agents that is — in the words of the Supreme Court — “so outrageous that due process principles would absolutely bar the government from invoking judicial process to obtain a conviction.” How outrageous? It would have to be so fundamentally unfair as to be “shocking to the universal sense of justice.”

Whatever that means. Maybe it’s like pornography. The Court can’t define it but will know it when it sees it.

I’m unaware of any similar motion ever having been granted. And I would be amazed if the Whitmer kidnap plot charges were dismissed.

But, by their motion, the defendants have raised the specter of a pre-trial hearing at which they may explore in detail the lengths to which the government went to manufacture a conspiracy that, left to the defendants’ own unaided devices, would have never progressed beyond the grumbling, griping, and loud talking stage. And demonstrating that alone would be a huge public service.

Finally, if the evidence at trial of FBI overreaching is substantially close to that described by the defense, the jury may be so offended by the government’s actions that they ignore the instruction regarding predisposition and find the defendants not guilty. Put another way, the defendants’ best but very slim chance of acquittal may well depend on nullification by a jury of ordinary citizens fed up with the Soviet-style provocations of our modern, woke, omniscient, and omnipotent FBI.

George Parry is a former federal and state prosecutor. He blogs at knowledgeisgood.net and may be reached by email at kignet@outlook.com.

Leave a Reply

Leave a reply.