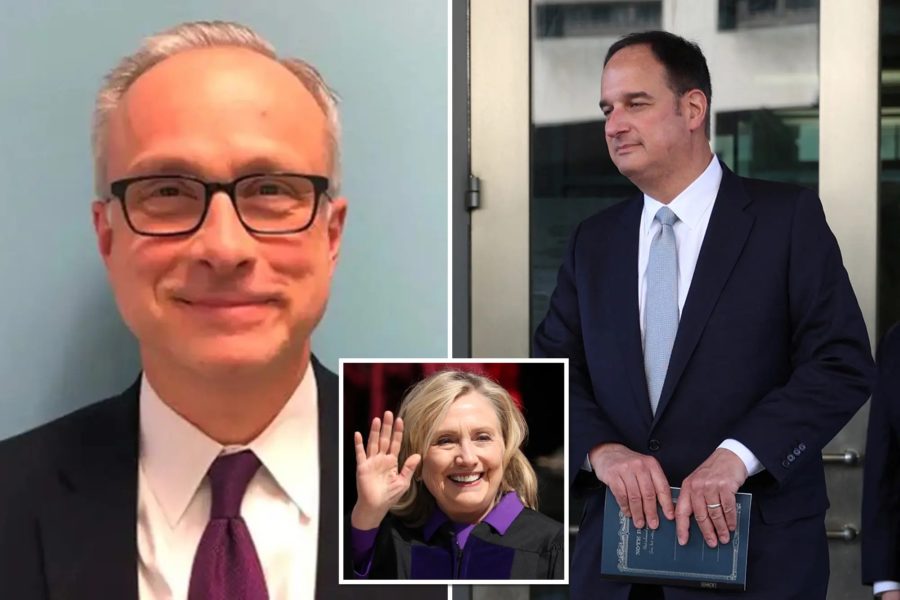

Yesterday, The American Spectator published my article about the trial of Clinton campaign lawyer Michael Sussmann. He has been charged with making a false statement to former FBI General Counsel James Baker. As expected, Sussmann elected not to testify in his own defense.

The case has gone to the jury which will resume deliberations when the court reconvenes after Memorial Day.

Here’s the article.

Michael Sussmann Remains Silent – The American Spectator | USA News and Politics

Ordinarily, in a criminal trial, the jury wants to hear from the accused. Although the court will instruct that no negative inference can be drawn if the defendant does not take the stand, as a matter of human nature, jurors still expect that, if he has nothing to hide, the accused will look them in the eye, proclaim his innocence under oath, and subject himself to cross-examination.

Nevertheless, with the advice of counsel, Clinton campaign lawyer Michael Sussmann has elected not to testify in his own defense. The reason for this move appears to be that he and his lawyers believe that they have already won the case. And that assessment may be correct.

Recall that Sussmann is charged with making a false statement when he met with then-FBI General Counsel James Baker on the eve of the 2016 presidential election. At that one-on-one meeting, Sussmann presented Baker with two thumb drives and a white paper setting forth contrived and misleading “evidence” of a secret communications channel between the Trump Organization and the Russian Alfa Bank.

Special Counsel John Durham’s prosecutors have put into evidence the following text message sent by Sussmann to Baker the day before the meeting:

Jim — it’s Michael Sussmann. I have something time-sensitive (and sensitive) I need to discuss. Do you have availability for a short meeting tomorrow? I’m coming on my own — not on behalf of a client or company — want to help the Bureau.

Baker has testified that he was “100% confident” that, at the meeting, Sussmann repeated that he was not providing the information on behalf of a client. He stated he believed that “it was pretty close to the beginning of the meeting” as “Part of his introduction to the meeting,” when Sussmann denied acting “on behalf of any particular client” as he turned over the bogus materials.

And it is that representation — that he was not acting on behalf of a client — that is the basis for the false statement charge against Sussmann.

Durham’s prosecutors have introduced evidence that the information provided to Baker was concocted by cybersecurity researchers working in conjunction with one Rodney Joffe, who was in line for a top government job if Hillary Clinton won the election. They have also introduced evidence that lawyer Sussmann billed the Clinton campaign for the time he spent meeting with Baker as well as for the two thumb drives.

In short, the prosecution has overwhelmingly established that Sussmann’s claim that he was not providing the information on behalf of a client was an outright lie.

But proving the lie is not enough. In order to convict, the jury must find beyond a reasonable doubt that, in violation of 18 U.S.C.§ 1001, Sussmann made a “materially false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or representation.”

So what does “materially” mean? According to the relevant case law, to prove materiality it is sufficient that the false statement had the capacity or a natural tendency to influence the determination required to be made by the government agency to which the statement was directed. It is not necessary to prove that the agency actually relied on the statement.

To be “material” means to have probative weight, i.e., reasonable likelihood, in influencing the agency to make a determination required to be made.

Thus, the test for materiality under 18 U.S.C. § 1001 is not whether the false statement actually influenced a government function but whether it had the capacity to influence.

In that regard, Baker testified that he probably would not have agreed to meet with Sussmann if he knew that the lawyer was acting on behalf of the Clinton campaign.

“That would raise very serious questions, certainly in my mind, about the credibility of the source and the veracity of the info — heightening, in my mind, whether we were going to be played or pulled into the politics,” Baker testified. “We were aware of and wary of being played — having the fact of our investigation being the thing to enable the press to report on something flawed or incomplete.”

While that testimony taken at face value proves the materiality of Sussmann’s lie, I expect that, in summation, Sussmann’s lawyers will attack Baker’s credibility based on a seemingly contradictory statement that he has made in other proceedings that he understood Sussmann to be speaking on behalf of clients.

Moreover, I expect that the defense counsel will argue that, despite the fact that FBI investigators quickly determined that the information presented by Sussmann was without merit, the FBI’s leadership was “fired up” about investigating Trump and were determined to go after him regardless of Sussmann’s lie.

Put another way, they will argue that Sussmann cannot be convicted of making a materially false statement since his claim that he was not representing a client did not actually influence the FBI’s decision regarding Trump. In short, they will argue that Sussmann’s alleged lie was not material since it fooled no one at the FBI (including Baker, who knew Sussmann) and had no effect on its top management’s decision to investigate Trump. Given the pro-Clinton bias of James Comey, Andrew McCabe, Peter Strzok, and others at the FBI, this argument would have a factual basis. (READ MORE: The Sussmann Trial Is a Window on Comey’s Clown Show)

Nevertheless, the jury can still convict if it determines that the lie had the capacity or natural tendency to influence the FBI’s decision. It is on that basis that the jury could determine that the lie was material and convict Sussmann.

What are the chances of that happening? Consider the following.

According to media reports, three of the jurors contributed to Clinton’s 2016 campaign. Another Clinton supporter is seated on the jury even though she expressed doubts as to whether she could be fair and impartial. The rest of the jurors are drawn from the District of Columbia, where, in the 2016 presidential election, Hillary Clinton won 90.9 percent of the votes compared to Trump’s 4.1 percent.

How inclined will such a jury be to convict Clinton’s lawyer when it would be so relatively easy for them to conclude that the prosecution did not prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Sussmann’s lie was material?

To ask the question is to answer it.

As Judge Taylor said in To Kill a Mockingbird, “People generally see what they look for and hear what they listen for.”

It is that truism that underlies the decision to keep Sussmann off the witness stand. Given the composition of the jury, he and his lawyers apparently believe that they’ve got this case in the bag.

George Parry is a former federal and state prosecutor. He blogs at knowledgeisgood.net and can be reached by email at kignet@outlook.com.

1 Comment

Leave your reply.